Sci-fi taxonomists take note: We are now officially in the Rare Earth Age of Science Fiction.

Technological change driving changes in human consciousness is not a trope, but a given. Philosophical arguments about organic consciousness versus AI take a back seat to practical considerations of how to deal with the inevitable robot apocalypse. We’re hip to the perils and tortures of the uploaded mind.

A couple of points:

- None of this is new. Purists would say the general leaning toward the cyberpunk(ish) dystopias of the Rare Earth Age started in print in the 1980s with the likes of William Gibson (and then, just to be contrary, you and I would skip over Phillip K. Dick and take it back to the virtual reality of Samuel R. Delaney’s Nova, and then further back to the transferred consciousness in Poul Anderson’s “Call me Joe”). What puts us so firmly in the Rare Earth Age is that the basic Rare Earth tropes are now the lingua franca of sci-fi television, often the last medium to be comfortably conversant with new elements in the sci-fi lexicon.

- Why Rare Earth? Because it fits. The rare earths are a group of seventeen chemically similar elements crucial to many high-tech products, including the device on which you are reading this. You’ve heard of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, of course, generally reckoned as the pulp heyday of the mid-1930s to the 1950s, or even as late as 1963. Everything after the Golden Age would be Silver Age or crappier. Everything before the Golden Age (think Jules Verne forward) has been dubbed the Radium Age—nicely done, that label, whether it sticks in the long run or not. The Rare Earth label describes the agent of change rather than relative value, and that agent of change is not the Radium Age juggernaut or the Golden Age rocket ship or Silver Age all-too-handy FTL / ansible. It’s right in front of you. The damned thing in your hand that’s changing your consciousness even as you read.

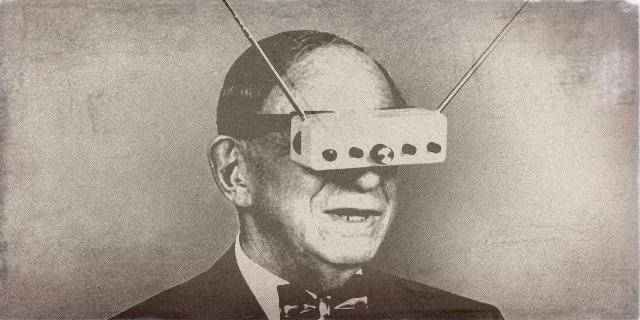

All the Rare Earth elements have trickled from print to your screen in a sci-fi language that includes its own visual shorthand. Take Black Mirror season 3 episode 4, “San Junipero.” One of the first images in the first scene is Max Headroom on a television in a shop window, so we know what we’re getting into (if the fact that it’s Black Mirror has escaped us). We infer quickly that the characters are interacting in virtual reality, and the script moves us swiftly and gracefully into the human drama of fully and finally uploading consciousness.

It’s very well done, a pleasant episode with a happy ending, a welcome relief from the unrelenting grimness of Black Mirror, especially following season 3 episode 3, “Shut Up and Dance,” in which internet trolling goes to a new and horrifying level when blackmailers use malware to take over a young man’s laptop. No spoilers, but that episode truly earned the use of the saddest song of the 1990s.

It’s not necessarily happy stuff. The use of Rare Earth devices is changing our lives, you see, not just our friendships and politics and shopping habits but our attention spans and the way our brains work, and television is catching up to those changes. The freedom to use the subtext of the Rare Earth Age allows television elbow room to delve into the nature of consciousness itself (shallowly and spastically, but still).

HBO’s Westworld is a theme park of proto-sentient-to-fully-conscious “hosts.” Unlike the menacing automatons of the original movie, this Westworld’s hosts are subtle creatures imbued with backstories (ostensibly to help them over the Turing test hump in the second year of development). Unlike the static park of the original movie, Westworld’s many threaded stories unravel for its guests like a complex, 4-D RPG, complete with branching story lines, campaigns, side quests, and Easter eggs.

Who would settle for less in a Rare Earth theme park?

Very interesting exchange near the end of season 1 between Ford, an architect of Westworld’s advanced androids, and the engineer Bernard, one of Ford’s creations who has become aware of his own mechanical origins:

Ford: Ever the student of human nature. I wonder, what do you really feel? After all, in this moment, you are in a unique position. A programmer who knows intimately how the machines work and a machine who knows its own true nature.

Bernard: I understand what I’m made of, how I’m coded, but I do not understand the things that I feel. Are they real, the things I experienced? My wife? The loss of my son?

Ford: Every host needs a backstory, Bernard. You know that. The self is a kind of fiction, for hosts and humans alike. It’s a story we tell ourselves. And every story needs a beginning. Your imagined suffering makes you lifelike.

Bernard: Lifelike, but not alive? Pain only exists in the mind. It’s always imagined. So what’s the difference between my pain and yours? Between you and me?

Ford: This was the very question that consumed Arnold, filled him with guilt, and eventually drove him mad. The answer always seemed obvious to me. There is no threshold that makes us greater than the sum of our parts, no inflection point at which we become fully alive. We can’t define consciousness because consciousness does not exist. Humans fancy that there’s something special about the way we perceive the world, and yet we live in loops as tight and as closed as the hosts do, seldom questioning our choices, content, for the most part, to be told what to do next. No, my friend, you’re not missing anything at all.

And there we have it. After most of a season peppered with tantalizing rubbish like references to Julian Jayne’s The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (and the other shoe: that bicameral mind theory had been “discredited”), we’re blithely ignoring the basic question: If your suffering and my suffering are indistinguishable, then how is your treatment of me justified?

Answer: I hereby discount the human experience of consciousness, and therefore it does not exist. Because our consciousness does not exist, your pain does not matter. It is what it is…and it is nothing.

Weak sauce, but served well, and at least we’re not in The Matrix. Or The Lawnmower Man.

I can relate to wanting simple answers to questions of consciousness and existence for television…and for my own so-called “life.” This cogito ergo sum / je pense, donc je suis business still bugs me. It not only assumes there is an “I,” (je, I reckon) but that there is some causal relationship between the “je” and the “pense“ – well, friends, that’s a couple of leaps I’m not willing to make. At best, I venture I can say, “C’est pensées, donc c’est pensées.” N’cest pas?

Don’t answer that. I don’t want to know.

But keep an eye on this one, this Rare Earth Age, won’t you? It’s making room for little wonders like Arrival (consciousness changing by dint of language acquisition, to which I can attest). Ping me if anything interesting happens. I’ll be here.